posted by Jürgen Kurtz, Justus Liebig University (JLU) Giessen, Germany

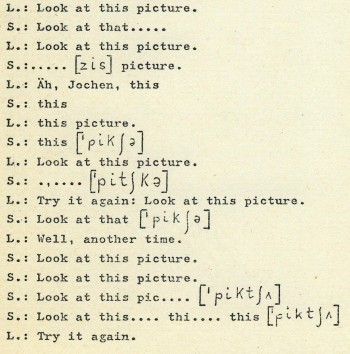

(S = student; L = teacher)

About a decade ago, my extremely influential academic teacher and esteemed mentor, the late Helmut Heuer (1932-2011), asked me to drop by his office at the University of Dortmund, on short notice, when I happened to be in town. I had just received my first professorship in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) at Karlsruhe University of Education at that time, after about ten years of working as a high school teacher in Dortmund, one of Germany’s largest cities. Since he had left me completely in the dark why he wanted to see me, I thought he was simply going to wish me good luck, and provide me with some further valuable advice, as he had done so often in previous years.

When I arrived in his office two weeks later, he immediately drew my attention to a pile of three old cardboard file folders, presented in a rather ceremonious fashion on the tiny table where he used to invite students to sit with him during his office hours. I must admit that the three folders did not look particularly interesting to me. They were stuffed to their limits and covered with dust. One of them had almost fallen apart. When he urged me to open them, I recognized that they were filled with English as a Foreign Language (EFL) lesson transcripts, written on a typewriter, dating back to the early 1970s, with hand-written remarks scribbled here and there. The paper on which the approximately forty transcripts were written had turned yellow with age so that some parts were difficult to read.

“It may not be obvious, but this is a treasure trove for research on learning and teaching English as a foreign language,” I remember him saying to me in German, referring to the pile as the unpublished ‘Dortmund Corpus of Classroom English’. “I would very much like you to have it”, he continued, adding that “there might be a time when you wish to take a closer look at it”. In the following conversation, he gave me some very general information about this apparently dated collection of classroom data, emphasizing that all lessons had been conducted in comprehensive schools (i.e. in non-selective lower secondary schools for children of all backgrounds and abilities) in the federal (West-) German state of North Rhein-Westphalia between 1971 and 1974.

Since our meeting was crammed between two of his classes, we did not have sufficient time to talk about the origins and the genesis of the corpus material in all the necessary details. So I sincerely thanked him and took the material with me to Karlsruhe. Mainly, perhaps, because this was my first professorship and everything was excitingly new and challenging, I somehow lost sight of the folders, keeping them stashed away in a safe place in my office.

In March 2011, I was appointed Professor of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) at Justus-Liebig-University (JLU) Giessen. While thinking about ways to enhance evidence-based or data-driven research in the field of foreign/second language education in the widest sense, I came across Olaf Jäkel’s work at the University of Flensburg. As a linguist interested in how English as a Foreign Language is actually taught in classrooms in Germany nowadays, he had just published the Flensburg English Classroom Corpus (FLECC) (see also Jäkel 2010) which comprises a total of 39 transcripts of English lessons given by pre-service student teachers in primary and lower secondary schools in Northern Germany, most of them in parts of the federal German state of Schleswig-Holstein.

This reminded me of the ‘treasure trove’ I was still sitting on, the unpublished lesson transcripts Helmut Heuer had so generously passed on to me so many years ago. I contacted Olaf Jäkel on this and was pleased to hear his positive and encouraging feedback to my initial thoughts about creating a digital version of the old documents. We agreed that making this historical collection of classroom data available to the international research community in a computer-readable format, publishing it as downloadable open access material on the Internet as well as a print-on-demand corpus, would be of considerable interest and value to anyone interested in or involved in researching authentic foreign or second language classroom interaction and discourse world-wide, both from a diachronic and synchronic perspective. I am grateful to him for co-funding the digitization of the classroom data, and for his generous support with publishing the book online and in print.

Scanning the original corpus material and converting the images into more easily searchable text turned out to be no longer possible. So the entire corpus material (more than 400 pages) had to be retyped again manually.

Reconstructing the setting in which the initial ‘Dortmund Corpus of Classroom English’ was assembled turned out to be both fascinating and difficult. Based on evidence from a variety of sources, including personal correspondence with participants directly or indirectly involved in the project, it soon became clear that the corpus project was launched in turbulent times, i.e. in the context of the ubiquitous school and education reform controversy which had been raging in former West Germany since the mid-1960s. At the heart of the controversy lay the polarizing issue of what constitutes equality of opportunity and effectiveness in education. Fierce political battles and scholarly conflicts over the crucial need to restructure the school and education system of the time eventually led to a large-scale, funded experiment with comprehensive schools which has come to be known as the (West) German Gesamtschulversuch. The complex process of setting up and implementing the first experimental comprehensive schools was accompanied with extended research (Wissenschaftliche Begleitung). The pre-digital corpus project represents a remarkable example of such accompanying research.

There is a sizable body of literature available (in German) today documenting and examining the large-scale school experiment which began in 1968 and ended in 1982. However, much of the published material focuses on general issues related to the definition and interpretation of comprehensiveness in secondary school education, the general and specific structure, aims, and objectives of comprehensive schooling, the link between structural and curricular innovations and reforms, the development and implementation of adequate curricula and instructional designs, and the efficiency and effectiveness of the newly established comprehensive schools as compared with traditional German secondary schools. Comparably little has been published to date illustrating and examining how (subject matter-) learning was actually organized and promoted in those new experimental schools, as for instance in the EFL classroom.

The DOHCCE (Kurtz 2013) contains a total of 36 annotated transcripts of English as a Foreign Language lessons conducted in German comprehensive schools prior to the communicative turn. Currently in print, it will be available in fall, both as open access data on the Flensburg University server and as a book on demand, published by Flensburg University Press. More on this in a few weeks. Please stay tuned.

Jäkel, Olaf (2010). The Flensburg English Classroom Corpus (FLECC). Sammlung authentischer Unterrichtsgespräche aus dem aktuellen Englischunterricht auf verschiedenen Stufen an Grund-, Haupt-, Real- und Gesamtschulen Norddeutschlands. Flensburg: Flensburg University Press.